La Donación

[2022]

Proyecto organizado por Co-net Art a través de su programa de residencias y coproducido por Consorci de Museus de la Comunitat Valenciana.

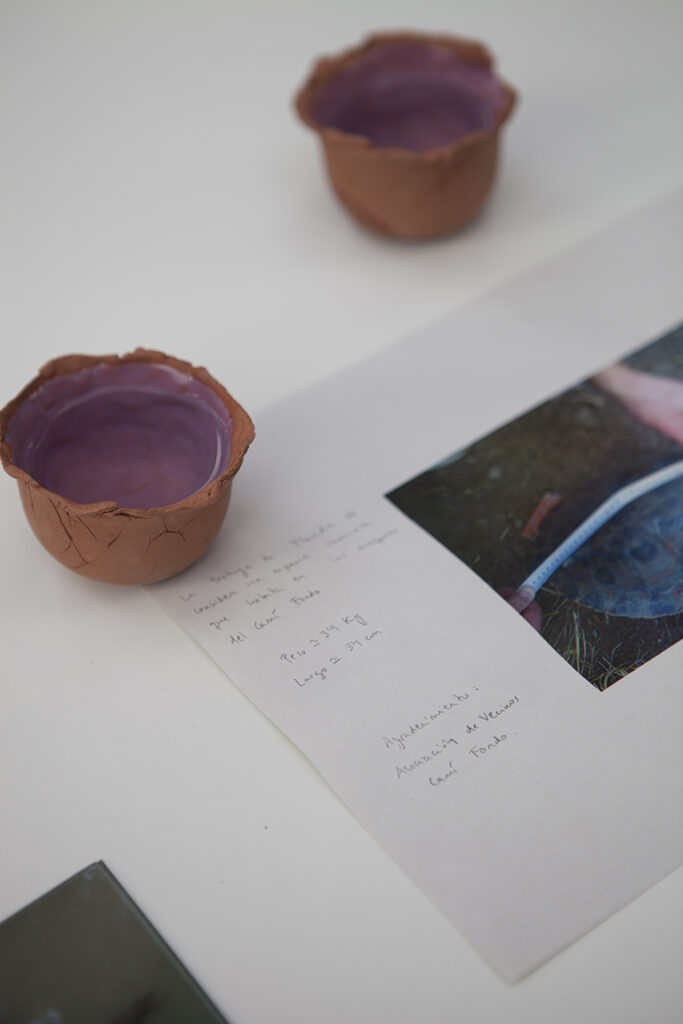

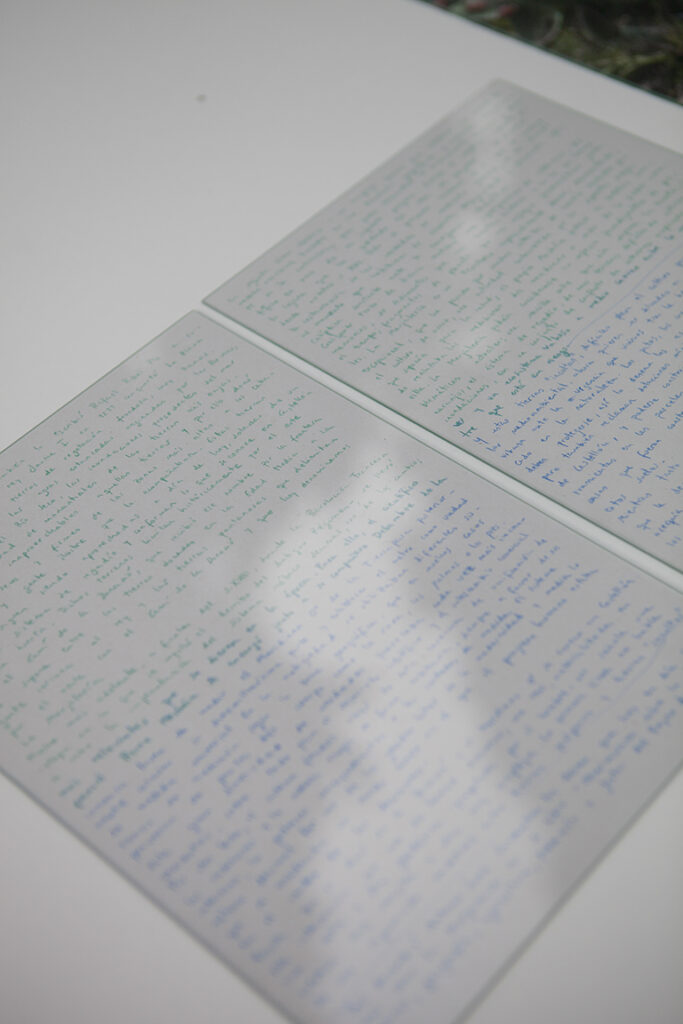

12 fotografías tomadas en digital a color, texto a lápiz sobre papel, cuencos de cerámica con agua recogida en La Marjalería, naranjas, dibujo a rotulador.

__________

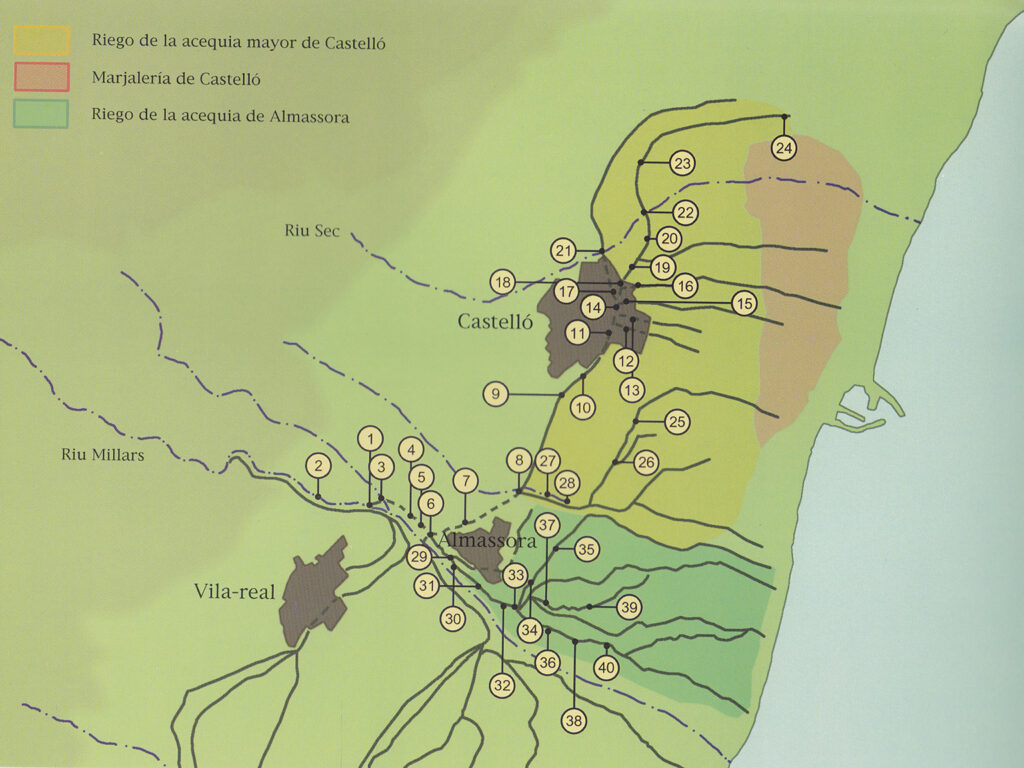

EN: Oral tradition has it, and it was also written by Rafael Ribés Pla in his book 'L'arròs a Castelló', that King James I in 1233 conquered La Plana and found a land of lush vegetation, very flat, in which there was a proliferation of stagnant water caused by rainfall, the overflowing of the Rio Seco, flooding from the sea and the large number of springs in the lower lands. The king considered those lands unusable and therefore donated the dry and firm lands of the higher areas to the knights, nobles and illustrious people who accompanied him. These prosperous lands are still being used today, equipped with a sophisticated irrigation system and make up what is known in Castellón as "La huerta". These lands are historically bordered to the east by the Camí de la Donació, which was so named because of the border between the lands donated in the Middle Ages to the people close to the king and the marshy lands that border the Camí de la Donació to the west and that today we call La Marjalería (the marshlands).

Much later, at the end of the 18th century, during the French Revolution -a stage in which the overthrow of the Ancien Régime was promoted-, the implementation of the decimal metric system was carried out, one of the most relevant changes that took place at that time. For this purpose, the french scientist Pierre Mecháin, together with his partner Delambre, undertook the immense task of measuring the 0º meridian of the Earth to later calculate its ten-millionth part and establish the meter as a universal unit of measurement. In ancient times different measurement systems were used depending on the geographical area, which in many cases came from parts of the body such as the rod, palms or feet. This great diversity of units caused more and more inconveniences, especially for scientific development and commercial exchange. On the other hand, the feudal system abused this lack of unification of measurements and the nobility chose arbitrarily, always in favor of their interests, the standards corresponding to the units of measurement. The decimal metric system was one of the great milestones of modernity and measured what was considered a new world in which human progress was at the center of decisions.

It turns out that the Camí de la Donació and the 0º Meridian intersect in Castellón. This intersection that joins two dividing lines; a real one, materialized in a street, and a geodesic one -projected by man- point us to a very simple and a very complex question: The first line tells us about a medieval separation between prosperous lands and "uncultivated" [1] lands. The second line obeys a complex process to establish a universal unit of measurement based on a geographical dimension and extracted directly from nature in order to develop human and scientific knowledge for the sake of a supposed progress. I write the adjective supposed because of how distant this idea of progress has become if we look at it from our 21st century. The whole modern project, which includes the establishment of global measurement units, has led us to the moment we live in of absolute inequality and constant apocalyptic sensation in the face of the climatic emergency.

Any piece of land contains a superposition of interests, of memories, of sediments that tell us stories and in which we read time; fragments of planet that reflect global problems. The Marjalería is a particularly dense, concentrated, exceptional territory that has undergone many attempts to make it profitable for rice cultivation, a controversial activity due to the alleged health risks; Mecháin himself died in Castellón while measuring the meridian due to yellow fever. La Marjalería could be considered a paradigmatic space of current problems: a simple street that still separates the orchard, the orange groves, the irrigation system, from land that is difficult to cultivate due to flooding, with a set of conflicts of interest that are complicated to resolve and a valuable ecosystem halfway between the marine and the terrestrial that is at risk.

And these "uncultivated" lands, difficult to cultivate but with a high environmental value, now want to be saved in an urban development plan in view of the urgency we are experiencing after the catastrophe we have caused in nature. The ducks, the cormorants, the native turtles must be protected, so wish the neighborhood associations in the area, but also claim minimum endowments as the rest of citizens of Castellón, and be able to build a hut to store their tools in the cultivation plots, also avoid the demolition of houses that were built prior to the qualification of these soils.

Meanwhile La Marjalería continues to flood every year because the water treatment plant can not admit all the water that comes down from the Rafalafena irrigation channel when it rains in Castellón, and also because the subway aquifers emerge forming the ullals, which literally means fangs in Valencian... Liters of water that remind us that no matter how many exact figures we use to study these floods thanks to our international system of measurements, orange trees grow better in the lands to the west of La Donación, in the areas that were ceded to the nobles many years ago. La Donation represents a border between privileges, the stratification of classes drawn on a map.

[1] This is how Antonio Josef Cavanilles described the lands we know today as La Marjalería in his book "Observations on the natural history, geography, agriculture, population and fruits of the Kingdom of Valencia".

________

ES: Cuenta la tradición oral, y también lo escribió Rafael Ribés Pla en su libro `L´arròs a Castelló´, que el rey Jaime I en 1.233 conquistó La Plana y se encontró con unas tierras de vegetación frondosa, muy llanas, en las que proliferaban las aguas estancadas originadas por las lluvias, los desbordamientos del Río Seco, las inundaciones procedentes del mar y la gran cantidad de manantiales de las tierras más bajas. El rey estimó inaprovechables aquellas tierras y por ello donó los terrenos secos y firmes de las zonas más altas a los caballeros, nobles y gente ilustre que lo acompañaban. Estas tierras prósperas siguen siendo aprovechadas a día de hoy, dotadas de un sofisticado sistema de regadío y conforman lo que se conoce en Castellón como “La huerta”. Dichos terrenos limitan históricamente por el este con el Camí de la Donació, que recibió ese nombre por la frontera que supone entre las tierras donadas en la Edad Media a la gente cercana al rey y las tierras pantanosas que delimitan por el oeste con el Camí de la Donació y que hoy denominamos La Marjalería.

Mucho más adelante, a finales del siglo XVIII, durante la Revolución Francesa -etapa en la que se impulsó el derribo del Antiguo Régimen-, se llevó a cabo la implantación del sistema métrico decimal, uno de los cambios más relevantes que se dieron en la época. Para ello, el científico francés Pierre Mecháin se encargó junto a su compañero Delambre de la inmensa tarea de medir el Meridiano 0º de la Tierra para posteriormente calcular su diezmillonésima parte y establecer el metro como unidad de medida universal. En la antigüedad se utilizaban diferentes sistemas de medición según la zona geográfica, que en muchos casos provenían de partes del cuerpo como la vara, los palmos o los pies. Esta gran diversidad de unidades provocaba cada vez más inconvenientes, sobre todo para el desarrollo científico y el intercambio comercial. Por otro lado, el sistema feudal abusó de esta carencia de unificación de las mediciones y la nobleza escogía de forma arbitraria, siempre a favor de sus intereses, los patrones correspondientes a las unidades de medida. El sistema métrico decimal fue uno de los grandes hitos de la modernidad y medía lo que se consideraba un mundo nuevo en el que el progreso humano estaba en el centro de las decisiones.

Resulta que el Camí de la Donació y el Meridiano 0º se cruzan en Castellón. Esta intersección que une dos líneas divisorias; una real, materializada en una calle y otra geodésica -proyectada por el hombre- nos señalan una cuestión muy sencilla y otra muy compleja: La primera línea nos habla de una separación medieval entre tierras prósperas y tierras “incultas” [1]. La segunda línea obedece a un complejo proceso para establecer una unidad de medida universal basada en una dimensión geográfica y extraída directamente de la naturaleza para poder desarrollar el conocimiento humano y científico en aras de un supuesto progreso. Escribo el adjetivo supuesto por lo lejana que ha quedado esa idea de progreso si la miramos desde nuestro siglo XXI. Todo el proyecto moderno, en el que se incluye la instauración de las unidades de medición globales, nos ha llevado al momento que habitamos de absoluta desigualdad y sensación apocalíptica constante ante la emergencia climática.

Cualquier trozo de tierra contiene una superposición de intereses, de memorias, de sedimentos que nos cuentan historias y en los que leemos el tiempo; fragmentos de planeta que nos reflejan problemáticas globales. La Marjalería es un territorio especialmente denso, reconcentrado, excepcional, que ha pasado por muchos intentos de hacerlo rentable para el cultivo de arroz, una actividad controvertida por los supuestos riesgos que suponía para la salud; el propio Mecháin falleció en Castellón cuando realizaba las mediciones del meridiano a causa de la fiebre amarilla. La Marjalería podría considerarse un espacio paradigmático de problemáticas actuales: una sencilla calle que aún separa la huerta, los naranjos, el sistema de regadío, de unos terrenos difíciles de cultivar por las inundaciones, con un conjunto de conflictos de intereses complicados de resolver y un ecosistema valioso a medio camino entre lo marino y lo terrestre que está en riesgo.

Y estas tierras “incultas”, difíciles para el cultivo pero con un alto valor medioambiental, ahora quieren ser salvadas en un plan de ordenación urbana ante la urgencia que vivimos tras la hecatombe que hemos provocado en la naturaleza. Los patos, los cormoranes, las tortugas autóctonas deben protegerse, así lo desean las asociaciones de vecinos de la zona, pero también reclaman dotaciones mínimas como el resto de ciudadanxs de Castellón, y poderse construir una casetilla para guardar sus herramientas en las parcelas de cultivo, también evitar el derribo de casas que fueron construidas de forma previa a la calificación de estos suelos.

Mientras tanto La Marjalería se sigue inundando cada año ya que la depuradora no puede admitir todo el agua que baja de la Acequia Rafalafena cuando llueve en Castellón, y también porque los acuíferos subterráneos afloran formando los ullals, que literalmente significa colmillos en valenciano… Litros de agua que nos recuerdan que por muchas cifras exactas que usemos para estudiar estas inundaciones gracias a nuestro sistema internacional de mediciones, los naranjos crecen mejor en las tierras al oeste de La Donación, en las zonas que ya hace muchos años se cedieron a los nobles. La Donación representa una frontera entre privilegios, la estratificación de clases trazada en un mapa.

[1] Así describió Antonio Josef Cavanilles las tierras que hoy en día conocemos como La Marjalería en su libro “Observaciones sobre la historia natural, geografía, agricultura, población y frutos del Reyno de Valencia”.

12 fotografías tomadas en digital a color, texto a lápiz sobre papel, cuencos de cerámica con agua recogida en La Marjalería, naranjas, dibujo a rotulador.

__________

EN: Oral tradition has it, and it was also written by Rafael Ribés Pla in his book 'L'arròs a Castelló', that King James I in 1233 conquered La Plana and found a land of lush vegetation, very flat, in which there was a proliferation of stagnant water caused by rainfall, the overflowing of the Rio Seco, flooding from the sea and the large number of springs in the lower lands. The king considered those lands unusable and therefore donated the dry and firm lands of the higher areas to the knights, nobles and illustrious people who accompanied him. These prosperous lands are still being used today, equipped with a sophisticated irrigation system and make up what is known in Castellón as "La huerta". These lands are historically bordered to the east by the Camí de la Donació, which was so named because of the border between the lands donated in the Middle Ages to the people close to the king and the marshy lands that border the Camí de la Donació to the west and that today we call La Marjalería (the marshlands).

Much later, at the end of the 18th century, during the French Revolution -a stage in which the overthrow of the Ancien Régime was promoted-, the implementation of the decimal metric system was carried out, one of the most relevant changes that took place at that time. For this purpose, the french scientist Pierre Mecháin, together with his partner Delambre, undertook the immense task of measuring the 0º meridian of the Earth to later calculate its ten-millionth part and establish the meter as a universal unit of measurement. In ancient times different measurement systems were used depending on the geographical area, which in many cases came from parts of the body such as the rod, palms or feet. This great diversity of units caused more and more inconveniences, especially for scientific development and commercial exchange. On the other hand, the feudal system abused this lack of unification of measurements and the nobility chose arbitrarily, always in favor of their interests, the standards corresponding to the units of measurement. The decimal metric system was one of the great milestones of modernity and measured what was considered a new world in which human progress was at the center of decisions.

It turns out that the Camí de la Donació and the 0º Meridian intersect in Castellón. This intersection that joins two dividing lines; a real one, materialized in a street, and a geodesic one -projected by man- point us to a very simple and a very complex question: The first line tells us about a medieval separation between prosperous lands and "uncultivated" [1] lands. The second line obeys a complex process to establish a universal unit of measurement based on a geographical dimension and extracted directly from nature in order to develop human and scientific knowledge for the sake of a supposed progress. I write the adjective supposed because of how distant this idea of progress has become if we look at it from our 21st century. The whole modern project, which includes the establishment of global measurement units, has led us to the moment we live in of absolute inequality and constant apocalyptic sensation in the face of the climatic emergency.

Any piece of land contains a superposition of interests, of memories, of sediments that tell us stories and in which we read time; fragments of planet that reflect global problems. The Marjalería is a particularly dense, concentrated, exceptional territory that has undergone many attempts to make it profitable for rice cultivation, a controversial activity due to the alleged health risks; Mecháin himself died in Castellón while measuring the meridian due to yellow fever. La Marjalería could be considered a paradigmatic space of current problems: a simple street that still separates the orchard, the orange groves, the irrigation system, from land that is difficult to cultivate due to flooding, with a set of conflicts of interest that are complicated to resolve and a valuable ecosystem halfway between the marine and the terrestrial that is at risk.

And these "uncultivated" lands, difficult to cultivate but with a high environmental value, now want to be saved in an urban development plan in view of the urgency we are experiencing after the catastrophe we have caused in nature. The ducks, the cormorants, the native turtles must be protected, so wish the neighborhood associations in the area, but also claim minimum endowments as the rest of citizens of Castellón, and be able to build a hut to store their tools in the cultivation plots, also avoid the demolition of houses that were built prior to the qualification of these soils.

Meanwhile La Marjalería continues to flood every year because the water treatment plant can not admit all the water that comes down from the Rafalafena irrigation channel when it rains in Castellón, and also because the subway aquifers emerge forming the ullals, which literally means fangs in Valencian... Liters of water that remind us that no matter how many exact figures we use to study these floods thanks to our international system of measurements, orange trees grow better in the lands to the west of La Donación, in the areas that were ceded to the nobles many years ago. La Donation represents a border between privileges, the stratification of classes drawn on a map.

[1] This is how Antonio Josef Cavanilles described the lands we know today as La Marjalería in his book "Observations on the natural history, geography, agriculture, population and fruits of the Kingdom of Valencia".

________

ES: Cuenta la tradición oral, y también lo escribió Rafael Ribés Pla en su libro `L´arròs a Castelló´, que el rey Jaime I en 1.233 conquistó La Plana y se encontró con unas tierras de vegetación frondosa, muy llanas, en las que proliferaban las aguas estancadas originadas por las lluvias, los desbordamientos del Río Seco, las inundaciones procedentes del mar y la gran cantidad de manantiales de las tierras más bajas. El rey estimó inaprovechables aquellas tierras y por ello donó los terrenos secos y firmes de las zonas más altas a los caballeros, nobles y gente ilustre que lo acompañaban. Estas tierras prósperas siguen siendo aprovechadas a día de hoy, dotadas de un sofisticado sistema de regadío y conforman lo que se conoce en Castellón como “La huerta”. Dichos terrenos limitan históricamente por el este con el Camí de la Donació, que recibió ese nombre por la frontera que supone entre las tierras donadas en la Edad Media a la gente cercana al rey y las tierras pantanosas que delimitan por el oeste con el Camí de la Donació y que hoy denominamos La Marjalería.

Mucho más adelante, a finales del siglo XVIII, durante la Revolución Francesa -etapa en la que se impulsó el derribo del Antiguo Régimen-, se llevó a cabo la implantación del sistema métrico decimal, uno de los cambios más relevantes que se dieron en la época. Para ello, el científico francés Pierre Mecháin se encargó junto a su compañero Delambre de la inmensa tarea de medir el Meridiano 0º de la Tierra para posteriormente calcular su diezmillonésima parte y establecer el metro como unidad de medida universal. En la antigüedad se utilizaban diferentes sistemas de medición según la zona geográfica, que en muchos casos provenían de partes del cuerpo como la vara, los palmos o los pies. Esta gran diversidad de unidades provocaba cada vez más inconvenientes, sobre todo para el desarrollo científico y el intercambio comercial. Por otro lado, el sistema feudal abusó de esta carencia de unificación de las mediciones y la nobleza escogía de forma arbitraria, siempre a favor de sus intereses, los patrones correspondientes a las unidades de medida. El sistema métrico decimal fue uno de los grandes hitos de la modernidad y medía lo que se consideraba un mundo nuevo en el que el progreso humano estaba en el centro de las decisiones.

Resulta que el Camí de la Donació y el Meridiano 0º se cruzan en Castellón. Esta intersección que une dos líneas divisorias; una real, materializada en una calle y otra geodésica -proyectada por el hombre- nos señalan una cuestión muy sencilla y otra muy compleja: La primera línea nos habla de una separación medieval entre tierras prósperas y tierras “incultas” [1]. La segunda línea obedece a un complejo proceso para establecer una unidad de medida universal basada en una dimensión geográfica y extraída directamente de la naturaleza para poder desarrollar el conocimiento humano y científico en aras de un supuesto progreso. Escribo el adjetivo supuesto por lo lejana que ha quedado esa idea de progreso si la miramos desde nuestro siglo XXI. Todo el proyecto moderno, en el que se incluye la instauración de las unidades de medición globales, nos ha llevado al momento que habitamos de absoluta desigualdad y sensación apocalíptica constante ante la emergencia climática.

Cualquier trozo de tierra contiene una superposición de intereses, de memorias, de sedimentos que nos cuentan historias y en los que leemos el tiempo; fragmentos de planeta que nos reflejan problemáticas globales. La Marjalería es un territorio especialmente denso, reconcentrado, excepcional, que ha pasado por muchos intentos de hacerlo rentable para el cultivo de arroz, una actividad controvertida por los supuestos riesgos que suponía para la salud; el propio Mecháin falleció en Castellón cuando realizaba las mediciones del meridiano a causa de la fiebre amarilla. La Marjalería podría considerarse un espacio paradigmático de problemáticas actuales: una sencilla calle que aún separa la huerta, los naranjos, el sistema de regadío, de unos terrenos difíciles de cultivar por las inundaciones, con un conjunto de conflictos de intereses complicados de resolver y un ecosistema valioso a medio camino entre lo marino y lo terrestre que está en riesgo.

Y estas tierras “incultas”, difíciles para el cultivo pero con un alto valor medioambiental, ahora quieren ser salvadas en un plan de ordenación urbana ante la urgencia que vivimos tras la hecatombe que hemos provocado en la naturaleza. Los patos, los cormoranes, las tortugas autóctonas deben protegerse, así lo desean las asociaciones de vecinos de la zona, pero también reclaman dotaciones mínimas como el resto de ciudadanxs de Castellón, y poderse construir una casetilla para guardar sus herramientas en las parcelas de cultivo, también evitar el derribo de casas que fueron construidas de forma previa a la calificación de estos suelos.

Mientras tanto La Marjalería se sigue inundando cada año ya que la depuradora no puede admitir todo el agua que baja de la Acequia Rafalafena cuando llueve en Castellón, y también porque los acuíferos subterráneos afloran formando los ullals, que literalmente significa colmillos en valenciano… Litros de agua que nos recuerdan que por muchas cifras exactas que usemos para estudiar estas inundaciones gracias a nuestro sistema internacional de mediciones, los naranjos crecen mejor en las tierras al oeste de La Donación, en las zonas que ya hace muchos años se cedieron a los nobles. La Donación representa una frontera entre privilegios, la estratificación de clases trazada en un mapa.

[1] Así describió Antonio Josef Cavanilles las tierras que hoy en día conocemos como La Marjalería en su libro “Observaciones sobre la historia natural, geografía, agricultura, población y frutos del Reyno de Valencia”.